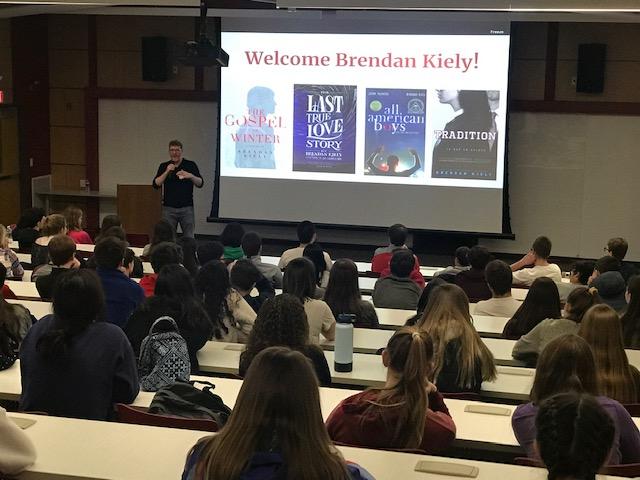

This March, I had the amazing opportunity to interview award-winning author, Brendan Kiely, following his second presentation to students. For forty-five minutes, we sat in the JDHS library and talked about his life, his books, and the topics he’s chosen to write about.

Blusk: Do you ever get writer’s block? If so, how do you deal with it?

Kiely: Yes, all the time, but I [also] don’t believe in it—I think it’s the fear that what you write will be bad—really bad, and… you need to give yourself permission to write garbage, even if it’s just blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, it’s setting the gears in motion—and even if you do end up throwing out all that work, you need words on the page, and you just need to push past it.

Blusk: What do you find the hardest and easiest thing to do in the writing process?

Kiely: I find the planning for the book to be easy, but sitting down to write and create the first draft is the hardest for me.

Blusk: How do you hope to see your books influence issues like the ones you write about such as rape and police brutality?

Kiely: I don’t think it can make the problem(s) go away, because I believe problems can be solved when groups of people can communicate better. What I hope is, my books can foster clearer and compassionate conversation between disagreeing minds.

Blusk: Do you have somewhere you keep track of all your ideas for books or subplots or characters, etc?

Kiely: One of the places I keep track of ideas is in notebooks; some on my desk [and] I have small notebooks that I keep with me in pockets of my coats. Sometimes, when I’m on the go, I’ll jot down things in my phone, and whenever I’m writing notes in small notebooks or my phone, I always take some time to translate those notes into a computer [later]. When I start to have enough notes about a story on my computer document, then I create a new folder that says something like untitled novel about —. The other place I have notes—at home—[are in] sticky notes all over the wall—all over the place.

Blusk: Out of all the current issues you could have talked about, why inequality, regarding feminism in your book Tradition and police brutality in All American Boys?

Kiely: In All American Boys I think it was because, as Jason and I were becoming friends, it was apparent that if a white man and a black man could tell the story together, we might be able to encourage more healthy conversations about how racism affects us. With Tradition, I was concerned that feminism was always left to women to talk about, and I wanted to write a book about how men could become better feminists.

Blusk: In your opinion, what’s the best way to hook a reader in the first sentence? Humor? Obscurity? Drama?

Kiely: So, one of my favorite sentences of all time is the first sentence of John Irving’s A Prayer for Owen Meany, and it goes something like this: “I remember the boy with the wrecked voice—not because he was the smallest person I’d ever met, nor because he was the instrument of my mother’s death, but because he is the reason I believe in God.”—That’s pretty powerful. In a sense, it actually is the plot of the novel in a nutshell, and for me, I believe—I try, to write first lines that teach the reader how to read the book. Humor is not my strong suit—I mean, I like humor—but I think, as a writer, sincerity is my strong suit, and so, for me, I lead with my strong suit. The takeaway line here, I think, is to lead with your strong suit, as a writer.

Blusk: If Jules or Bax were real and you were face to face with them right now, what would you say to them? Would you give them any advice?

Kiely: I think to Jules I would say: I believe you, never give up, and you get to define your life. And to Bax, I would say—and I’m thinking about this after the end of the book—I would say: I appreciate you, and I hope you can encourage more guys to listen and think about how they can truly love their friends—and I say that because, for me, of course, as I was writing Tradition and about the experiences of men and how, at least for me growing up, guys were really trained to not think about love. And the way that I was always trained to think about love was always love between an intimate partner, when I should have thought about love more as between friends between boys and girls or any gender or fluidity in there, and so it’s too bad that some men think of love as an uncomfortable word.

Blusk: Let’s say you were either face to face with Rashad, Quin, or the police officer from your book All American Boys. What would you say to them?

Kiely: I would speak to Officer Deluso, and I would say: I’m sorry, I want you to know I feel bad for you too, and to be the hero you say you want to be, we need you to tell the truth, and in order to tell that truth, it might mean having to listen to the stories of people who have experiences with you from their perspective—not how you want them to perceive you, but rather how they really perceive you.

Blusk: What would you say to white people who think it isn’t their place to talk about brutality against black people?

Kiely: I would say that we should affirm the leadership and wisdom of folks of color in conversations about racism, and be courageously mad with them about the racism and brutality that exists in our society, and echo that courage when we find ourselves in situations in which the room is predominantly white, so that we don’t rely only on people of color to tell their truths, but rather, we amplify their truths in spaces where they are not or when they’ve been silenced—and we have the opportunity to amplify that truth. Because the problem is that sometimes we have the opportunity and folks of color don’t, so we have to own up to that opportunity.

Blusk: Do you think that teaching high school has influenced your writing? If so, how?

Kiely: Absolutely. I love spending time with teenagers, because the way that young children will say “Hey! That’s not fair!”—I often find young adults, teenagers, will say “I want to make the world more just” or “I want to do something to help make the world a better place.” Spending so much time around young adults inspires me to want to do the same, and not grow old—cause that’s the easy thing.

Blusk: How do you think that your books would be impacted if you were an African American or a woman?

Kiely: For me, as someone who is neither of those things, I want to write stories in which characters who share those elements of my identity are learning from the truth of others. So in order to do that, I have to have folk that aren’t like me in the books—women and people of color in the books. So, if I were a woman and/or a person of color, it’s likely the stories I would write would center on women and people of color and I’d be speaking from my own experience. And sometimes that would give me more authority, but sometimes, people wouldn’t want to hear me speak. Therefore, that’s why I write about people like me that learn how to be better listeners.

Blusk: In previous interviews you’ve talked about feminism regarding your book Tradition. In your opinion, what does feminism mean?

Kiely: Sidebar, when I was in college we talked a lot about the feminist majority, and what we talked about is that feminism is simply a world in which men and women are treated equally, and I still, to some degree, agree with that—a world in which men and women are treated equally—but for me, now, I would amend that definition a little, and I would say that feminism should be about the empowerment of women and people who identify as non-male to have the freedom to live with full agency, and not have their lives defined in some way or another by people who identify as male. That’s different than the previous definition because equality is a thing that people have a hard time with—and often people will have a really hard time because they only use one example, and one example is not the same as hundreds and thousands of examples we could talk about, so equality is the wrong word—equality isn’t the same thing is justice.

Blusk: With rape being something that more and more people are conversing about, do you think that impressionable young boys will be positively or negatively affected by this?

Kiely: Well, truthfully, I think some will be negatively affected, and I think some, if not many, who are good-hearted people who don’t mean any harm will now have a language for how to be better friends, partners, family members, to the women in their lives. I’m contextualizing that particularly around the kind of binary, male-and-female experience in rape culture, but obviously it’s broader.

Blusk: How did you come upon writing Tradition?

Kiely: So, there are three things. The first is the national news story of the Saint Paul school in New Hampshire. Chessy Prout wrote a memoir about her experience at Saint Paul’s—and I’m talking about my inspiration for it [Tradition] is, in fact, her story—so I want her to get credit for telling her own story—I didn’t know she was going to write a memoir—and I was interested in writing about it—it struck me as equally important—but 2, it wasn’t only Chessy Prout’s story—by the way, her book is called I Have The Right Too—anyway, but 2, it wasn’t just her story, I realized that her story was so similar to many other’s stories, and so I was inspired by the idea that so many traditions, schools, and institutions in the country were enabling men in particular to foster and perpetuate rape culture. Because, at the same time that I was listening to Chessy Prout’s story, I was listening to women in my life around me begin to share “This is what happened to me” , “This is what happened to me” , “This is what happened to me” and before that even got started on a national level —though, just so we should all be aware: the #MeToo movement has been going on for more than a decade—but for me I was listening to the women in my life that were closest to me saying “This is what happened to me” so I wanted to write about that.

Blusk: Do you think that there would be fewer cases of police brutality if the police force consisted of more black people?

Kiely: Yes, it’s factually true that in Washington D.C Marion Barry—who is a very controversial figure—made some changes—that people policed neighborhoods that they were from, so if you were in a neighborhood that was prominently black, you’d also be from that neighborhood—and statistically that lowered the issues. However, there were still problems. So, yes, I think it’s true, and, it’s also true that black cops will still perform the problems of racism if they’re stuck in a racist institution. So it’s not only a solution to get more folks of color on the force, but rather, we have to address implicit bias in law enforcement.

Blusk: In past interviews you’ve often repeated the phrase “How can men be better feminists?” In your opinion, how do you think men can be better feminists?

Kiely: 1. Learn how to be better listeners. 2. Be quiet so that someone else can talk. 3. Affirm realities that make them feel uncomfortable, meaning, if a girl says “I feel this way” or, even “you did this and I was uncomfortable”—choose to affirm other people’s realities before getting defensive. 4. Choose to stand up and affirm those women’s truths in situations where the room is mostly male.

Blusk: What was it like co-authoring with Jason Reynolds?

Kiely: It was amazing. Jason is a tremendous human being… and man… friend, and idol—someone I admire, and writing with someone like that is an opportunity of a lifetime. And it’s exciting because—it’s like basketball—Jason and I are two, and there’s one defender ahead of us, and we are passing that ball back and forth, waiting to see who’s going to get the ball before the lay-up. And we want to set the other person up to make the most spectacular layup or dunk possible, and that’s what writing the book was like—about passing the ball to set up the other partner to enable the spectacular dunk. Our writing process was built on trust, and we couldn’t have written that book if we hadn’t become friends first, so, writing with him was writing with one of the closest friends in my life—but it was a surprise to have found him as one of my closest friends.

Blusk: Is there a specific reason why you chose teenagers to be the protagonists of your books?

Kiely: I’m inspired by teenagers, and so I want to write books that inspire them too.

Blusk: Do you plan on co-authoring with anyone in the future, like with what you did in All American Boys?

Kiely: I would be happy to, if the situation comes up.

Blusk: What was your life like growing up?

Kiely: I grew up in predominantly white middle class in a part of the country that thinks of itself and describes itself as very open minded and liberal, and the reason why I mention all this is because I learned that I was in fact incredibly sheltered, and my understanding of the world was very limited. Which is, in fact the case, for many, many people depending on where it is that they grew up—that they grow up in a bubble, wherever that bubble might be—not everybody, but many people, and I think back to the heroes of my childhood, and the lessons that I learned, and realized how some of my heroes were only telling me part of the story, and not because they were wrong or malicious, but that they, too, were maybe sheltered, and so part of what I love about how I grew up was also how my parents had always instilled in me a sense of curiosity and a value to listen to other people so that I can be a better friend, a better partner, but also, by listening to others, I can me a better me. So growing up, for me, I think the biggest question for me was learning how to get outside of myself.