Contributing Writer Alethea Shirilan-Howlett, ’20

Marcia Brady. Zack Morris. Hailey Dunphy. Teenagers. The often rebellious, sometimes weepy, always lazy generation that just has to learn to put on a happy face for the real world in order to be successful in it. At least, that’s what they’re told. That philosophy is buried in the majority of high schools and colleges in America, and it’s going to hurt the next generation of adults who will enter the workforce.

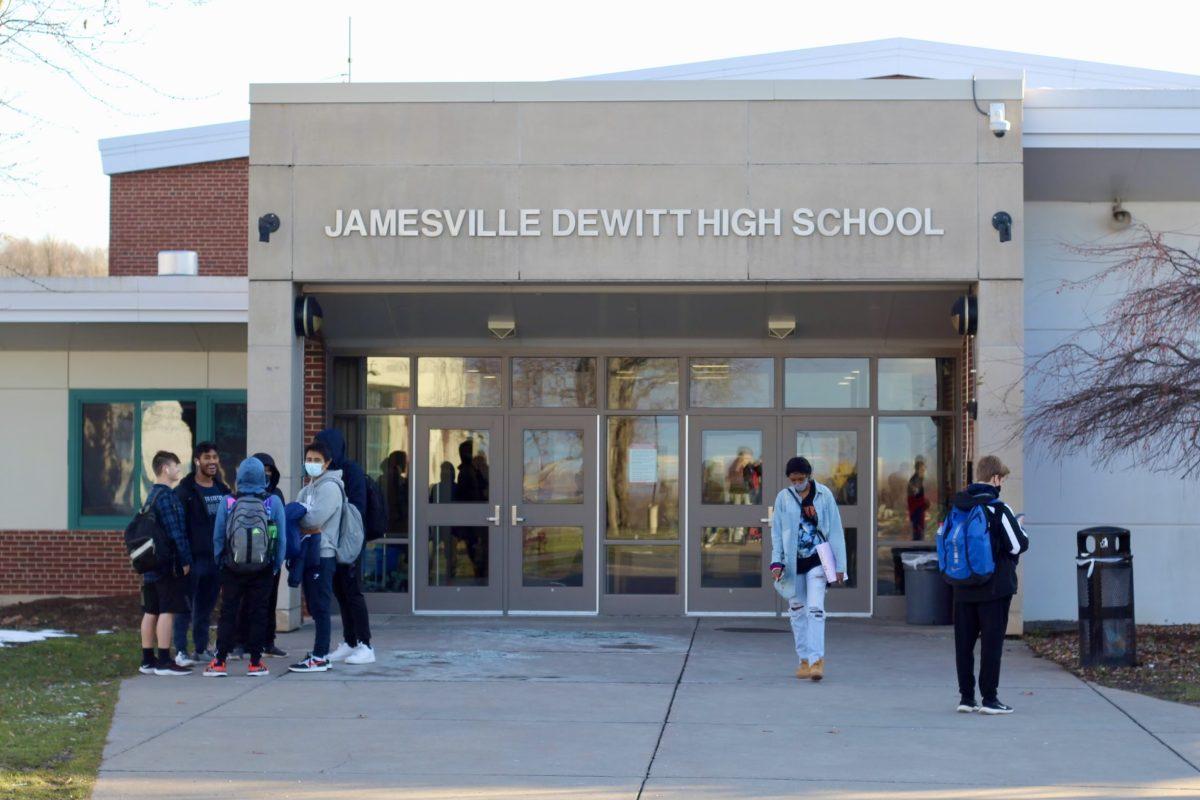

The model of a high achieving student, in high school or in college, holds a backpack full of textbooks and more in her hands. He is involved in many extracurricular activities, and she is an active volunteer in her community. He is smiling. One can see them on any average pamphlet sent to prospective freshmen advertising a college, or on a Google Image search for “student”. The idea of this “model student” as the standard for a teenage applicant, unbothered by the inconceivable amount of work that weighs on their backs and is held in their hands, is sending the wrong message to students everywhere.

A study from UCLA, conducted by UCLA sociology professor S. Michael Gaddis, showed that campuses with higher stigma around mental health treatment had very few students seek treatment. His research included six years of data on 62,756 students from 75 different institutions. The students were asked how likely they were to think less of someone if they had a mental illness. The same students also answered questions that indicated whether or not they had been diagnosed with a mental illness or had attempted self-harm. Gaddis said, “This indicates that in places where their peers are stigmatizing mental health treatment, students do not want to even acknowledge their mental health struggles.” This mental health crisis is happening because of the failure of an entire education system to properly address teen mental health.

The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), signed into law in 2002, gained support for its advocacy for a better education for English-language learning, poor, minority children, who were falling behind in school compared to their peers. NCLB’s true aim was to make America academically competitive again. This law, if adopted by a state, required standardized testing in schools. The results of these tests were supposed to aid schools in bringing all students up to the “proficient” level (although, that standard, too, was decided by the state). NCLB was repealed in 2015, but the havoc it wreaked on guidance counselors’ position in many American high schools remains.

In a study done by two assistant professors of counseling, Colette Dollarhide and Matthew Lemberger, school counselors were interviewed in the context of NCLB. One was quoted as saying, “Teachers are more stressed, which filters down to the students. I am seeing more students having difficulty with teachers. I see a lot of discouraged students who have difficulty testing and don’t see a future in high school.” On their own job at their school, one counselor stated, “I am in charge of all testing (counselor and proctor). I am not able to work on the three domains of school counseling, while I have been given a lot of the administrative assignments for NCLB.” The substitution of a guidance counselor, who aids students with their mental health needs, with a proctor for an exam is indicative in itself of how education systems have failed to make mental health a priority.

Today’s teenagers have slightly more to worry about than the social risk of wearing braces or who’s going to ask them to the dance. The current generation of teenagers are the people America will entrust to find solutions to the looming threat of climate change. Why are we treating them so badly? How do we fix the problem? The solution is talking about mental health. The best way to reduce stigma around a topic is to destigmatize. To normalize and acknowledge that a large percentage of the world’s population suffers from a mental illness — 450 million people — would be a major step in the right direction.

When these teenagers are able to seek help, it will not only be better for humanity, but the economy as well. A study from the Harvard Business Review showed that while $17 billion to $44 billion is lost to depression each year, $4 is returned to the economy for every dollar spent caring for people with mental health issues.

Instead of buying into stereotypes about teenagers that have been perpetuated for generations, let’s set them up for true success by making sure their mental health is advocated for and cared for.