The United States’ Electoral College was instituted in 1787 for two reasons: to create a balance between large and small states, and to decrease the electoral power of the U.S. citizenry. Today, the advantage given to small states disenfranchises marginalized communities by giving disproportionate power to rural white voters. Further, in the modern age, the idea that the average American is too dumb to vote is antiquated and anti-democratic. While there is no educational attainment data from 1787, the percentage of Americans aged 25 and older with a high school diploma increased from 41% to 91% between 1960 and 2021.

Under the Electoral College, a group of electors in each state cast their ballots for the presidential candidate chosen by their state’s popular vote. The number of electors per state is based on the amount of senators and representatives from that state. In most states, political parties nominate a slate of electors at a state party convention. If that party’s candidate wins the state’s popular vote, that party’s electors are bound by various state laws to cast their ballots according to the popular vote. In Maine and Nebraska, rather than adopting this “winner-take-all” system of electors, the electoral votes are cast in direct proportion to the state’s popular vote. Out of the 538 Electoral College votes (100 Senators, 435 voting representatives, and three non-voting representatives from D.C.), a majority of 270 is required to win the presidency.

A glaring oversight in the Electoral College is the lack of regulation regarding electors. Specifically, “faithless electors” can cast their ballot against their state’s popular vote without punishment. Despite 29 states and D.C. explicitly forbidding electors from casting their ballots in opposition to the state’s popular vote, a Colorado federal court decided that states cannot penalize faithless electors. This case, known as Baca v. Hickenlooper, set the precedent for faithless electors to ignore the will of the people and vote based on their own beliefs.

The most common criticism of the Electoral College is that candidates can win the presidency without winning the popular vote. In the event that neither candidate receives 270 electoral votes, the House votes and chooses the president. More specifically, each state delegation – the group of the state’s representatives, votes for one of the top three candidates. This can be problematic when the House does not choose the candidate with the most electoral votes. In the “corrupt bargain” of 1824, John Quincy Adams made a deal with Henry Clay to defeat the frontrunner, Andrew Jackson. Adams offered Clay a job as secretary of state if Clay gave his support in the House to Adams. Thus, Adams won despite trailing Jackson by a staggering 10% in the popular vote.

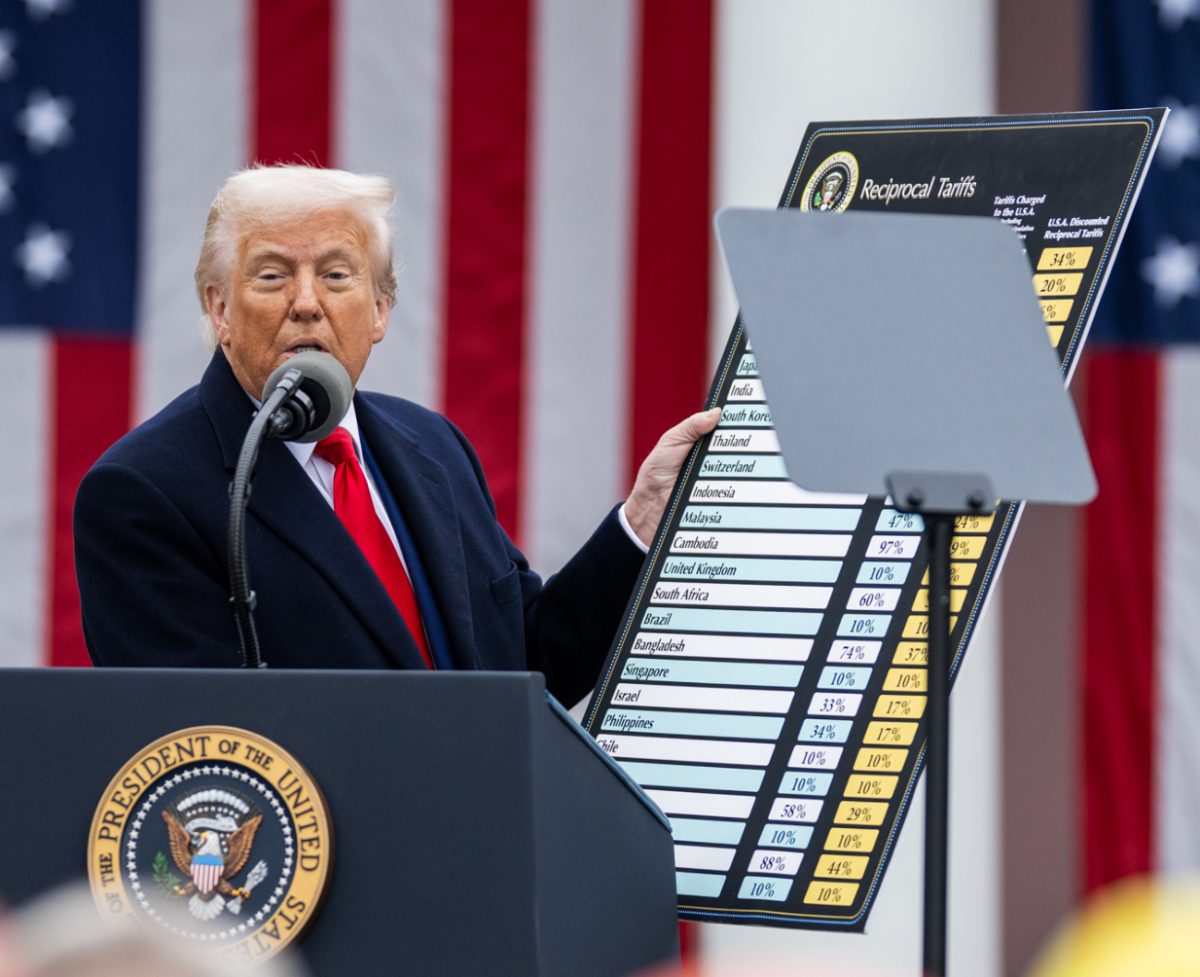

More recently, in 2016, Donald Trump beat Hillary Clinton by 74 electoral votes despite losing the popular vote by roughly three million votes. This disparity stems from Trump’s advantage in small states. For example, Democratic stronghold California has roughly 700,000 people per electoral vote, while Republican-controlled Wyoming has roughly 200,000 people per electoral vote. In small states like Wyoming, one person’s vote counts more than three times as much as in large states like California.

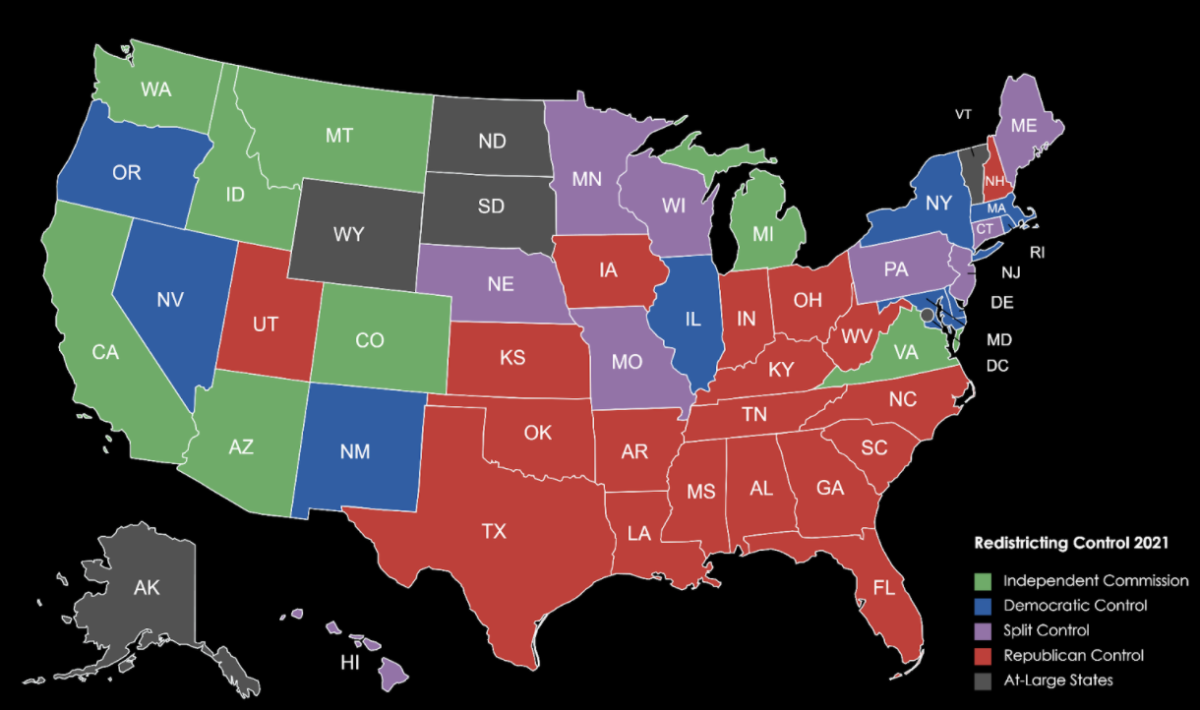

Because most small states lean Republican, the debate over the electoral college has become highly partisan. A 2019 Politico poll found that 72% of Democrats support switching to a direct popular vote, while only 30% of Republicans support this change. This makes it nearly impossible to abolish the Electoral College, which is enshrined in the Constitution. While the U.S. came close to abolishing the Electoral College in the past, this would not be possible today as two-thirds of the House and Senate, and three-fourths of the states would have to agree on an amendment.

In the absence of federal action, some states are taking electoral reform into their own hands. Crucially, the Constitution does not dictate that electors must vote in accordance with their state’s popular vote. This is how Maine and Nebraska are able to reject the “winner-take-all” system adopted by every other state. Since 2008, 15 states and D.C. have signed the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC), agreeing to cast all their electoral ballots according to the nationwide popular vote, rather than the state’s popular vote. This means that all states bound by the NPVIC must vote for the same presidential candidate. Thus, if NPVIC states eventually comprise 270 electoral votes, the candidate with the most popular votes will win the electoral college. This would effectively nullify the Electoral College, although thanks to Baca, faithless state electors could vote against the national popular vote without repercussions. Due to this possibility, the NPVIC would likely have to gain far more than 270 electoral votes to create a buffer against faithless electors, which is highly unlikely given the Republican advantage in the Electoral College.

While there is little hope for a constitutional amendment changing the electoral process, the best chance the U.S. has to make the process more representative is getting more states to sign the NPVIC. All NPVIC signatory states pass identical laws requiring its electors to vote with the national popular vote. Unfortunately, the NPVIC does not address the complications that could arise if a non-signatory state chooses electors in a way that makes it impossible to objectively tally the popular vote. It assumes that there is a simple way to count the popular vote in every state, but because states can choose electors however they choose, they could choose to undermine the count of the national popular vote. This is what Alabama did in the 1960 election, when its Democratic convention chose five pledged Democrat electors and six unpledged electors to make up its slate of 11. The state then put the names of the electors on the ballot, rather than the presidential candidates. This scheme made it impossible to know which presidential candidate was preferred by residents who voted for the unpledged electors. Because of the narrow margin of the popular vote in the 1960 election, the reported result of the popular vote actually varied based on the source. For the NPVIC to succeed, it would need to change its laws to address the issue that could be presented by a rogue state selecting its electors in an uncommon way.

If the Electoral College is ultimately abolished by Congress, or its issues nullified by state efforts, a key question arises: What should replace it? The most common answer is the national popular vote. While the national popular vote is preferable to the Electoral College, it is not the best option. Hypothetically, let’s say there are three candidates running for president. Candidate A is a Democrat and Candidates B and C are Republicans. If Candidate A receives 40% of the popular vote, while Candidates B and C each receive 30%, the Democratic candidate would win despite 60% of the country favoring the Republican Party.

The better alternative, which would require a constitutional amendment, is ranked-choice voting. In this system, voters rank every candidate in order of their preference. If one candidate has a national majority of first choice rankings, that candidate wins the presidency. However, if no candidate has a majority in the first round, the candidate with the fewest first-choice votes is eliminated, and voters who selected that candidate as their first choice have their “first choice” votes transferred to their second choice candidate. Then, the next candidate with the fewest first choice votes is eliminated, and the process repeats until one candidate has a majority. The ranked-choice voting system is more likely to reward a candidate with a broad appeal to the most citizens, and it is less likely to produce “spoiler” candidates who seek to draw support away from a major party, allowing the other party to win.

Until support for a constitutional amendment can be garnered, ranked-choice voting will be relegated to a few local and state elections. Meanwhile, the U.S. will likely see an increase in faithless electors after the Baca decision, thereby decreasing the impact of the popular vote. If enough states sign a version of the NPVIC that addresses the loophole of unconventional elector selection, it would massively increase the power of the U.S. people to choose their president. And with regulations limiting the number of candidates on the ballot from each party, it could prove successful. But until the U.S. presidential electoral process is heavily reformed, it will continue to discount the voice of the people.