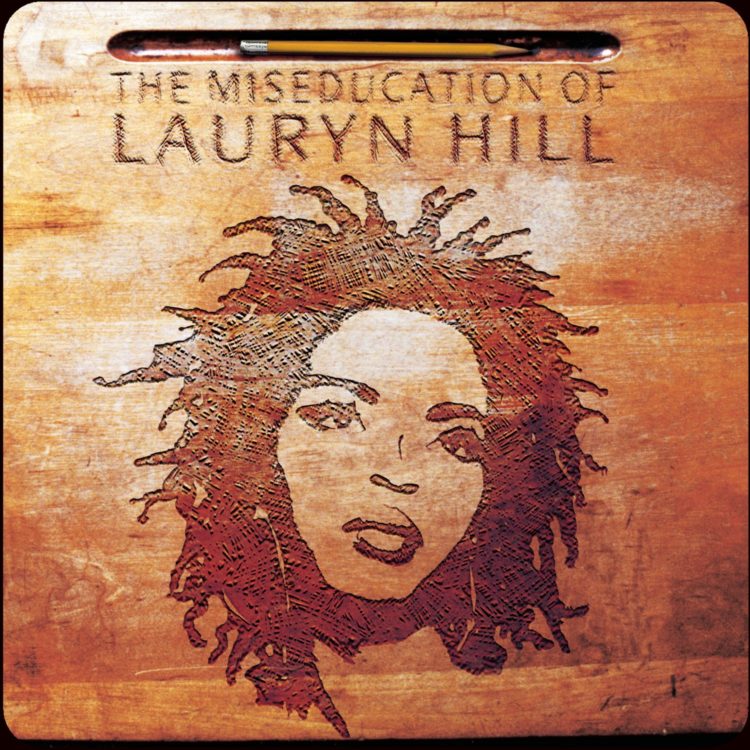

The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill by Lauryn Hill

Analysis by Luke Hobika ’20

7.96/10

Is it more advantageous to be street smart or book smart? Should a person rely on others to resolve their own problems? Will the facts in textbooks better prepare a person for life, or will the learning from their personal experiences benefit their future?

On her debut and only solo effort, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, Lauryn Hill tackles this question with a determined attitude in order to find an answer. However, her attitude comes as a result of her own faults in life rather than the matters that plague society as a whole. The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill serves as an intrinsic journey for Hill, exposing her scars in an attempt to gain insights for herself as well as for those whom she cares most. The album has been garnered by fans and critics alike for being the initial project of the neo-soul genre. Instrumentally, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill steadily infuses the sounds of a variety of musical genres, including funk on “Every Ghetto, Every City, jazz on “Superstar,” and hip-hop on “Lost Ones.”

Lyrically, the album is a progressive narrative of Hill finding herself by carefully examining the momentous moments of her life. Most notably, the skits that scatter themselves throughout this album, which are small dialogues between a teacher and his students about the meaning of love, highlight the contrast in her upbringing and the orthodoxy method of raising a child. In absence is Hill, who is missing out on the class’ exploration of the topic, leaving her lacking any knowledge regarding what love really is. Throughout the majority of the tracks that make up the first half of the fourteen-song album, a fragile Lauryn Hill takes note of her vulnerabilities before utilizing her own mishaps to overcome her difficulties. The solemn and oppressed lyrics of tracks like “Ex-Factor” showcase Hill being susceptible under the thumbs of those with whom she surrounds herself, leaving her as a self-conscious follower rather than a prosperous leader. Additionally, Hill embarks on the topic of self-doubting and missed opportunities on dismal tracks like “When It Hurts So Bad,” where she mentions the detrimental impacts of the insensitive comments and actions of highly-regarded individuals on the internal thoughts on others. As the project advances, Hill metamorphosizes into her own self. In the process, she draws inspiration from her greatest joys (“To Zion”), her disgust in regards to the state of the status of women in society (“Doo Wop (That Thing)”), as well as the monotonous dynamic of the music community (“Superstar”). The numerous tracks of self-admittance and individual realizations eventually lead to Hill’s discovery of herself. Now able to comprehend her own thoughts and actions, Hill works towards abandoning her past faults and ridding the sources of stress in her life through forgiveness. “I Used To Love Him” consists of a now mindful Hill condemning her previous actions involving past lovers, including clever metaphors like that of her being the sand and her lover being the ocean, forcefully pulling her in against her will. Furthermore, rather than chastising those who were the source of Hill’s issues, Hill absolves their actions on tracks like “Forgive Them Father,” maturely preventing any later drama from occurring. In the end, the mood and subject of the track “Everything Is Everything” completely juxtaposes those of the opening songs. Instead of releasing words of self-discouragement, Hill voices a glass-half-full approach to life with optimistic lines such as “After winter must come spring” and “Let’s love ourselves and we can’t fail/To make a better situation.”

When addressing the main theme of the album, it is simple to acclaim the tracks as a whole in their contribution to the meaning of the project. The theme aside, the faults of some tracks and their overall contributions to the album are made conscious. Throughout the tracklist, there are several instances of filler songs that offer no connection to that given moment on the album. For instance, the dull “Nothing Even Matters” is smooshed in between the buoyant “Every Ghetto, Every City” and “Everything Is Everything,” two tracks that are supposed to represent Hill climbing out of her own bottomless pit. The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill would not have suffered from having a chunk of its 78-minute duration shaved off. Yet as Hill preaches, it is crucial that a person looks passed both their own imperfections and the shortcomings of those with whom they involve themselves. Therefore, the listener should not allow the inconveniences of The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill hamper their overall experience. Instead, the listener ought to invest themselves into Hill’s vocalization of the advocations for life.