After a year and a half of the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers have figured out a way to conduct a real-world trial testing the effectiveness of wearing masks at preventing the coronavirus. Following pushback from Republicans against mask-wearing, proof finally exists that they really work against COVID. It has been difficult to do a study such as this because social cues and reminders are necessary to get people to wear masks consistently over an extended period of time, but they have succeeded by randomizing whole communities rather than the individual.

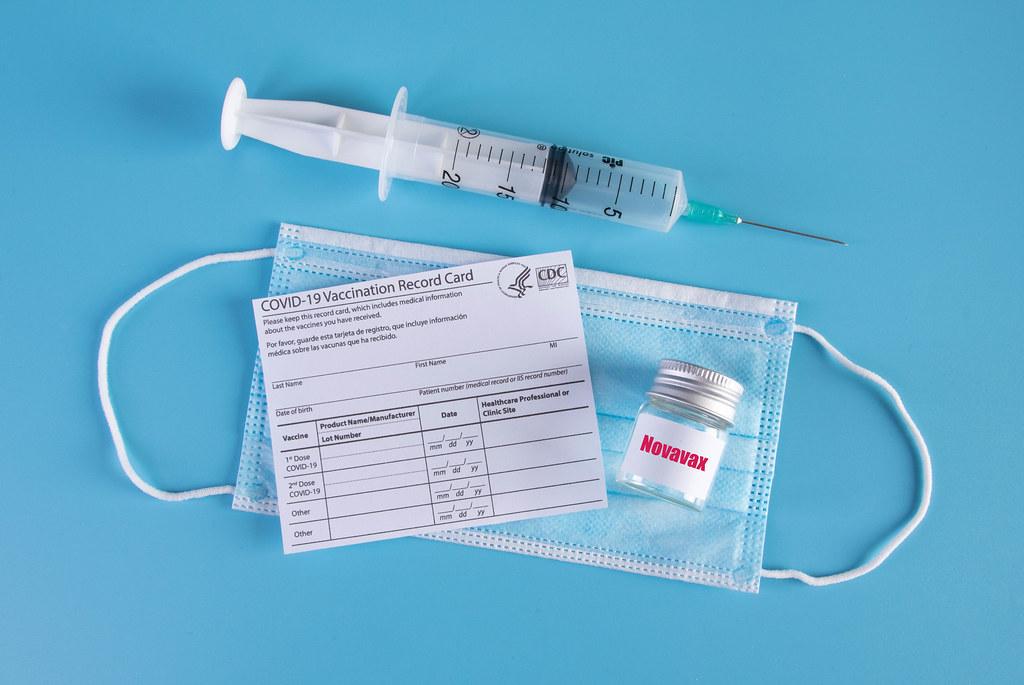

A group of university researchers recently published the findings of their community-based randomized-controlled mask trial in Bangladesh. The real-world study, conducted over eight weeks from November, 2020 to January, 2021, included 600 communities (some urban and suburban, some rural; all with roughly the same population) and 342,126 adults. The researchers gave half of the villages cloth or surgical face masks (one-fourth of total villages got each respective type) and reminded them to wear the masks properly. The other half of the villages got no masks. The villagers who received masks were shown videos of popular Bangladeshi figures endorsing the masks to encourage their use. Blood tests of symptomatic villagers during the trial tracked COVID-19 infections.

Previous studies have shown that people are not truthful about wearing masks in public. To solve this issue, rather than asking the villagers whether they wore masks, the researchers observed the villagers’ mask use in person throughout the trial in public places such as mosques and markets. In fact, the researchers also observed mask usage in rural Bangladesh areas in two waves months before the trial, and they found that mask-wearing dropped from 51% in May, 2020 to 26% in June, 2020 in the areas they observed. The Bangladesh government mandated mask-wearing in May, but after they barely enforced it in rural areas, mask usage dropped. This demonstrates the need for encouragement and promotion of mask-wearing in these rural areas, as well as any campaign of this type.

The villages that received masks had about 9% fewer symptomatic cases of COVID. Although this figure seems low and insignificant, the researchers believe it was an underestimate, because they did not test asymptomatic or mild cases. Another factor that could have contributed to an underestimate of mask efficacy was that only one third of symptomatic individuals agreed to take a blood test. Not all the villagers participated, so not all potential cases were counted. Infection rates were low in Bangladesh at the time of the trial, and the prominent strain was the original coronavirus (Alpha), which is less transmissible than Delta, which has since taken over in the area. Because Delta is more transmissible, more potential COVID cases could have been prevented by mask-wearing if the trial had been conducted a few months later. In reality, only 42% of those in the villages assigned to wear masks actually wore them, and 13% of those in villages not assigned to wear masks were already wearing masks, so the campaign increased mask-wearing by only 29% and still produced a 9% reduction in COVID cases. Just changing the behavior of 29% of people made a big difference. If 100% of people wore masks in Bangladesh and the math scaled accordingly, around 30% of COVID cases in the country would be prevented.

Researchers noted that masks were more effective for older villagers. People aged 50-60 years who wore surgical, rather than cloth, masks were 23% less likely to test positive for COVID than those who wore no masks. For those older than 60 who wore surgical masks, the reduction in infection risk was 35%. Many Americans have refused to wear masks because they believe masks don’t protect them, but this trial proves that these surgical and cloth masks protect the wearer, not just others.

A further finding was made about the efficacy of cloth masks versus surgical masks. Villages that received surgical masks had 11% fewer recorded cases than those which received no masks, while villages that received cloth masks only saw a reduced infection rate of 5%. The masks given to the villagers were tested by the researchers in a lab as well. The cloth masks had a filtration efficacy of 37%, while the surgical masks had a filtration efficacy of 95%, on par with N95s and KN95s.

Findings of the trial go even further. Researchers found that four factors were most effective at promoting mask-wearing in the Bangladeshi villages: distributing free masks, offering information through videos and local leaders, reminding people to wear masks in public and encouraging them to wear them correctly, and modeling proper mask use via local political and religious figures. These measures increased the rate of mask-wearing in villages that received masks from 13% to 42%. Villagers evidently became accustomed to wearing masks, as mask-wearing remained 10% higher among the intervention group five months after the trial. Physical distancing, also encouraged by the researchers, increased from 24% in the control (no masks) group to 29% in the intervention (masks) group.

The Bangladeshi trial, among many other things, proved that saving lives equals saving money. According to Ashley Styczynski, a doctor at Stanford who collaborated on the study, it costs $10,000 in masks and public campaigns to save one person’s life who would have otherwise died from COVID-19. That may be expensive in a poor country such as Bangladesh, but spending $10,000 on mask distribution and promotion could keep people out of hospitals using the government’s money (if the country has universal healthcare). Keeping more people healthy and out of hospitals will keep them working and contributing to the economy.

The researchers also gave behavioral nudges to the participants. Some households were instructed to put a sign up declaring that they were a mask-wearing household. Some households received text reminders to wear masks. Village leaders were given $190 or recognition by the government of Bangladesh if mask-wearing reached a target level. Some households received altruistic (selfless) messaging while others were promised self-protection. In villages without signage, two-thirds of the households were asked to promise to wear masks in public. None of these nudges were found to have any effect on mask-wearing above the core intervention.

The results of the study affirmed what scientists have been saying: masks are effective at preventing COVID-19 and surgical masks are better than cloth masks. Because of this groundbreaking trial, the public now has a broader understanding of COVID-19 preventative measures.