Recently, the AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson (J&J) COVID-19 vaccines have been linked to a rare form of blood clot, but only in rare cases. A blood clot occurs when platelets in the blood attempt to patch bleeding. This attracts other platelets, which also attempt to stop bleeding and clump in one area. Blood clots are actually beneficial, as the platelets work to combat injuries and cuts by plugging the injured blood vessel. However, some types of clots form without a seemingly good reason, and these can require medical attention and can cause great pain. The clots associated with the vaccines have surfaced in the brains of the affected people, and they are linked to low platelet counts.

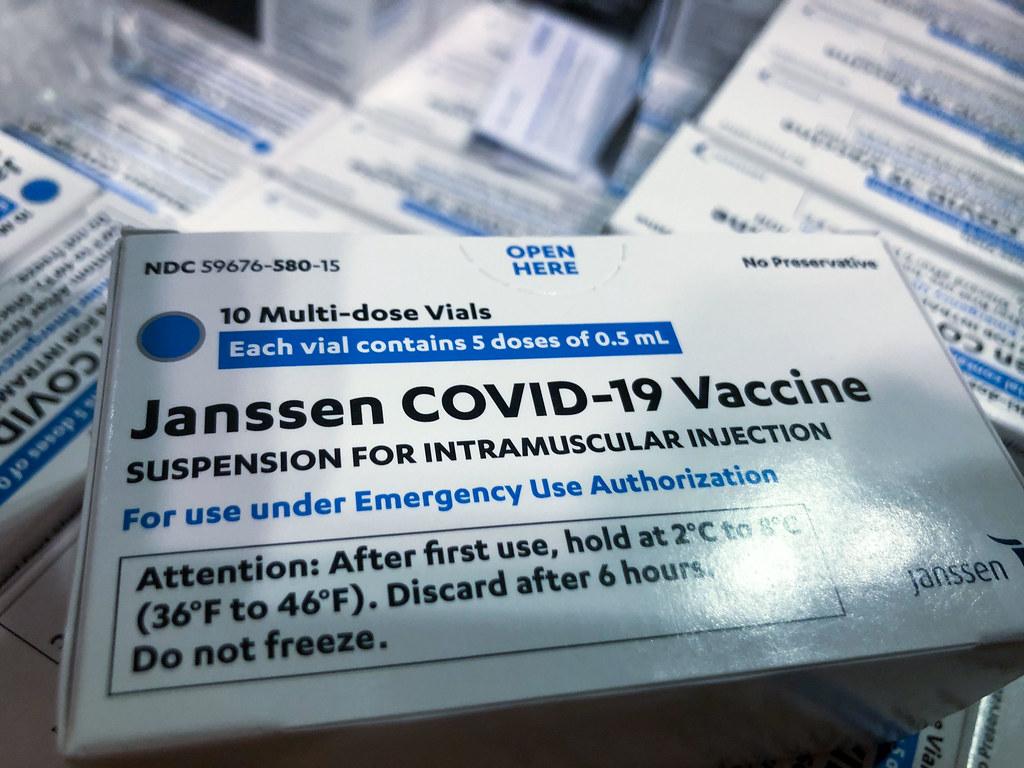

These clots, called cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, affect around 2-5 people per million each year. These particular clots can be life-threatening, although vaccines are usually not a cause for this type of clot. As of April 4, 2021, 16 people out of the eight million Americans vaccinated with the J&J vaccine have developed these rare blood clots. WIth regard to the J&J vaccine, the clots occurred between six and 13 days after immunization (single dose). Most of the clots caused by both vaccines occurred in younger to middle aged women, with only one man being confirmed to have developed a clot from the vaccine as of April 30.

Meanwhile, European health officials have reported that the AstraZeneca vaccine, which has not been approved in the U.S., has caused about 200 cases of clotting. Both the J&J and AstraZeneca vaccines use a harmless type of virus called an adenovirus to instruct the human body on how to fight COVID-19. This similarity has led health experts to believe that the viral vector (adenovirus) and the blood clots could be linked.

To put the rareness of the clotting into perspective, in terms of vaccinated people, there is approximately a four out of one million chance of death, which is the same risk of getting murdered in the next month in the U.K. Using a birth control pill increases the chance of getting a blood clot more than the vaccines. The birth control pill increases the risk of getting a clot by a factor of four. However, these clots caused by the pill are less deadly than the rare clot caused by the two vaccines in extremely rare cases.

Doctors do not yet know why the clots are appearing more frequently in women than in men, nor what puts people at risk for the clots. This same type of clot can occur in people who did not receive one of the vaccines, although it remains very rare. It is known that women are three times more likely than men to suffer from one of these clots without receiving a vaccine. Thus far, researchers believe this is because of birth control or other hormonal restrictions that women take, hence why it shows up in younger or middle-aged women.

Researchers believe that this low-platelet clotting is similar to a reaction some individuals have when they receive a blood thinner called heparin. Doctors often use heparin to thin a person’s blood in the event of a heart attack or a blood clot when blood flow needs to be reestablished. Some people, however, have the opposite reaction, and their blood instead clots more. This happens because the body triggers an unwanted immune response to the heparin, believing it to be a foreign invader. When the unnecessary antibodies attach to the heparin and the platelets, the body believes it needs to repair an injury. Thus, as even more platelets are used up, blood clotting can occur. When doctors looked at the blood of patients who developed clots after receiving one of the two vaccines, they found that it looked similar to the blood of people that have reacted adversely to heparin, suggesting that an unwanted immune response could be caused by the J&J and AstraZeneca vaccines, in very rare cases.

This side effect of blood clotting has halted vaccination efforts worldwide, albeit briefly. This has been problematic in the European Union (EU), which has centered much of its vaccination effort around the AstraZeneca vaccine. Wealthier member states were not able to offset this with their supply of Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, but poorer EU members could not, at least not on short notice. The AstraZeneca vaccine was halted in Europe in early March, and resumed on March 18 by the EU. The J&J vaccine halted rollout in the EU in April, but it was also re-approved in about a week. According to a recent YouGov poll, 61% of the French, 55% of Germans, and 52% of Spaniards consider the AstraZeneca vaccine “unsafe,” which could prove to be a hindrance. The pausing of vaccinations in Europe occurred as the continent experienced a surge in cases. The EU has reportedly chosen not to renew its vaccine contracts with J&J and AstraZeneca after this year.

On April 13, the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a joint statement with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which advised that rollout of the J&J vaccine be paused in the U.S. (the AstraZeneca vaccine has not yet been approved in the U.S.). However, the recommendation was lifted on April 23 thanks to the low number of blood clotting cases due to the vaccine. Additionally, some countries limited the use of the AstraZeneca and J&J vaccines to older people, as they say it is more important for older people to get vaccinated no matter what.

AstraZeneca has said 17 million people had so far received their vaccine, and the blood clot incidents were “much lower than would be expected to occur naturally in a general population.”

Meanwhile, in response to the blood clots, Johnson & Johnson Chief Scientific Officer Paul Stoffels said, “As the global pandemic continues to devastate communities around the world, we believe a single-shot, easily transportable COVID-19 vaccine with demonstrated protection against multiple variants can help protect the health and safety of people everywhere. We will collaborate with health authorities around the world to educate healthcare professionals and the public to ensure this very rare event can be identified early and treated effectively.”

Things may be improving, as doctors in Denver have discovered a method of treating the blood clots caused by the J&J vaccine. The patient was treated with bivalirudin, a blood thinner. Her platelet count steadily increased, and she was soon released from the hospital. As concerns have been raised over the vaccines, scientists and experts have advised that vaccination should continue using the AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson vaccines, as they are still safe in well over 99.9% of recipients.