With the arrival of the long-awaited first COVID-19 vaccine, many are eager to get the promising shot. The first vaccine, made by pharmaceutical giant Pfizer (fī-zer), has already reached hospitals and nursing homes across the country, and has been administered to the first round of recipients. Many are concerned, however, about the vaccine, worried that it has been rushed out to the general population, who are the real test subjects. Rest assured, 43,000 people were the actual test subjects of this vaccine, and it looks quite favorable.

The great vaccines of the last century have generally been made in the same ways. They train the body to fight infections by administering a small dose of the germ, or something like it, into your body. This allows the body to make antibodies, unique proteins that have a perfect design to bond to one thing, the germ. Because of this, the body remembers that it has fought the germ before, and when your immune system has fought something before, it becomes much faster and more aggressive at fighting it in the future.

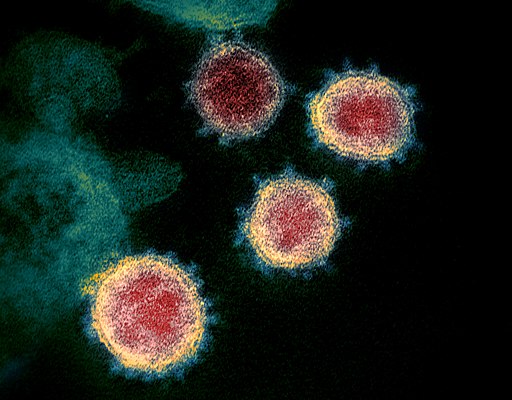

The coronavirus itself is made of specific RNA genetic material, wrapped in a lipid (fat) membrane. On the surface of the membrane are some spiky proteins. These proteins are just the right shape to connect with the proteins on the surfaces of human cells, which allows the virus to invade human cells. With the virus’s genetic material inside human cells, the genetic instructions take over the cell, telling the cell to make more of the virus.

The vaccine against coronavirus has a novel strategy. Instead of injecting the germ or something like the germ, vaccine recipients are really being injected with a specially-crafted form of messenger RNA, or mRNA. The mRNA vaccine particle fuses with the lipid bilayer of the human cell membrane, allowing it to enter the cell. Once inside, the mRNA meets up with ribosomes, which are instructed by the mRNA to create the spike protein for coronavirus. This effectively gets the coronavirus spike protein into the body, so that the immune system can learn how to fight it by making antibodies against the vaccine-generated spike protein. In the future, if a vaccinated person faces the real coronavirus, these antibodies it’s learned to make can bind to the real spike proteins lining the outside of the virus, rendering them unable to attach to human cells. This is the first vaccine to ever work by injecting mRNA, rather than the germ or something similar.

All this was a theory about how to make a quick, novel vaccine, but it turns out to be highly effective. The prestigious New England Journal of Medicine published the results of the Pfizer study, looking into the efficacy and possible side effects of the BNT162b2 vaccine. The vaccine was tested in roughly 43,000 persons, aged 16 and over, in four countries (the United States, Brazil, Argentina, and South Africa), who were healthy or had stable chronic medical conditions. Half were randomly assigned to receive the vaccine, while the other half received a placebo, or dummy medicine, a shot of saltwater in this case. Patients did not know which one they received, nor did the doctors treating them. All participants, both vaccine and placebo recipients, received two shots administered 21 days apart. Researchers followed participants for four months after vaccine or placebo administration in order to assess exclusively new cases of COVID-19.

Out of 36,523 participants who showed no evidence of prior infection, eight cases of COVID-19 were recorded in those who got the vaccine, and 162 cases occurred in those that received the placebo. Thus, those randomized to the vaccine suffered 154 fewer cases of COVID-19 than expected, a 95% effectiveness at infection prevention. Additionally, among 3,500 participants who previously had a coronavirus infection, the vaccine was also proven to prevent future cases of the virus.

The Pfizer researchers also looked for adverse effects, such as safety issues or side effects to the vaccine. Serious adverse effects were found in 0.6% of vaccine recipients, and in a comparable 0.5% of placebo recipients, with severe fatigue being the most common. Among lesser side effects, they looked for adverse events such as fatigue, headache, fever, and pain at the injection site. After the first dose, 83% of those who got the vaccine complained of pain at the injection site, while just 14% of placebo recipients complained about the same symptom. Of vaccine recipients, 47% complained of fatigue while 33% of placebo recipients did the same. Recipients who complained of headache included 42% of those vaccinated and 34% of placebo responders. These responses were among the younger participants, with ages ranging from 16 to 55. In participants aged over 55, adverse effects were similar, but slightly less common. Pain at the injection site remains a side effect of any shot, to some extent, although pain was far worse for vaccine recipients versus placebo. Less than 1% of participants in each group reported fever after the injections. Results between the first and second doses were very similar. However, these mild to moderate side effects of the Pfizer coronavirus vaccine are similar to those of other vaccines.

In addition, the Pfizer researchers looked to see if the vaccine performed differently among a variety of sub-groups. But whether male or female, caucasian or hispanic, North or South American or African, healthy or obese, young or old, there was little variation in the favorable results.

While the Pfizer vaccine was the first vaccine to reach the general public, it is not the only one to do so. The second FDA-approved vaccine, also an mRNA vaccine, made by biotechnology company Moderna, began use in hospitals and nursing homes on December 20th. The Moderna study of roughly 30,000 patients has not yet been published.

Much remains to be seen regarding the effect of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. It is still unknown whether those who are vaccinated can still transmit the virus to others. Other potential side effects could still emerge as the vaccines reach a broader audience. Regardless, mass vaccination with the Pfizer vaccine has begun, and many remain hopeful that vaccines will enable people to return to normal COVID-free lives.