At a college open house event, I was invited to spin a wheel to win a prize. I won a webcam cover, which is a cover for one’s laptop camera. I had never seen one before. After doing some research, I found out that webcam covers have a surprising fan- former FBI director, James Comey. “I put a piece of tape — I have obviously a laptop, personal laptop — I put a piece of tape over the camera,” he said in an interview at Kenyon College. It seems pretty paranoid to block one’s personal camera, but once an FBI director reveals that he does it, being that paranoid just might be justified. Really, the systems that the U.S. government uses to access the information of its citizens are built on paranoia. After the 9/11 attacks, it was discovered that the CIA previously had access to potentially life-saving information —two of the suspected terrorists had come to the United States several months before, and were not caught. That intelligence never reached the FBI. The U.S. began heightening their surveillance in the face of Islamic terrorism and began implementing new surveillance programs. Because of the way these programs were put into place, the functionality of U.S. surveillance has been hindered for almost 20 years.

One of the first of these programs, the Terrorist Surveillance Program, was created in the immediate years after the 9/11 attacks and allowed for government officials under the Bush administration to intercept and eavesdrop on phone calls. In 2005, that program was discovered to have been eavesdropping on an interaction between two parties based in the U.S., regardless of the requirement by the White House at the time that one end of the call must be from another country. In 2007, the Attorney General of the U.S. claimed that any electronic surveillance that was occurring as part of the Terrorist Surveillance Program would be conducted subject to the approval of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, or FISC, from then on.

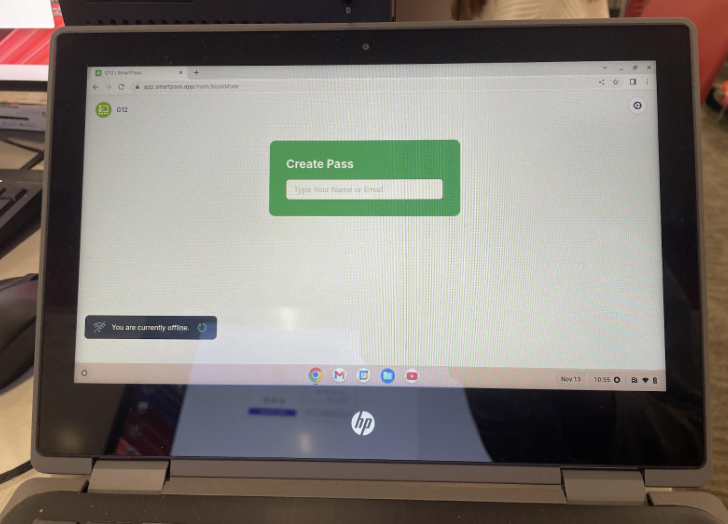

It became clear that the government had been abusing their power to search and collect data in June 2013 when Edward Snowden, a former CIA agent, leaked top-secret NSA information to The Guardian. This leak exposed a secret replacement to the Terrorist Surveillance Program: a program called PRISM that was not subject to the same judicial oversight by the FISC. Beginning in 2007, PRISM, which stands for Planning Tool for Resource Integration, Synchronization, and Management, began demanding the collection of information from Internet companies such as Facebook, Apple, and Google. Along with PRISM, the Snowden leaks revealed that the NSA can tap into one’s personal devices without notice, even if those devices are not connected to the Internet. Yes, the NSA can surveil users through laptop cameras — and it can do much more than that. The Snowden leak revealed the existence of an NSA program called Optic Nerves, a bulk surveillance program under which webcam images were captured and then “stored for future use” every five minutes from Yahoo users’ video chats. Between 3 and 11 percent of the images captured contained “undesirable nudity”. These outright spying maneuvers are direct violations of the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States. The amendment states that “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated.”

To get around this, the NSA has manipulated the wording of the fine print they are bound to. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 Amendments Act of 2008 states that “An acquisition (of information) may not intentionally target any person known at the time of acquisition to be located in the United States”. However, much of the data that the NSA has collected from U.S. based persons has been labeled as “incidental,” that this data was supposedly unintentionally collected when gathering research. This FISA bill was most recently renewed in Section 139 of the FISA Amendments Reauthorization Act of 2017. This act essentially gives the NSA permission to keep collecting information “incidentally”. It won’t expire until 2023.

It’s true that surveillance is a necessity of the information age—we’re just implementing it in the wrong way. Especially given the rise of violent attacks on minority groups from perpetrators who often participate in suspicious activity online, we need to focus on the way we do surveillance now more than ever. As an active member of my Jewish community, the 2018 attack on the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh haunted me for weeks on end. This was the deadliest attack on the Jewish community in American history. I was extremely disturbed by the fact that the gunman in the Pittsburgh shooting had been extremely active online before the shooting, sharing his anger toward Jews to the Internet. I was also shocked by the similarities to Pittsburgh in a shooting at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas in August 2019. The El Paso shooter posted his response to the “Hispanic invasion of Texas” in a four-page manifesto online. From 2017 to 2018, extremist-related murders spiked 35 percent and in 2018, every one of those murders was carried out by a right-wing extremist. While privacy is a Fourth Amendment right, that right can also allow for domestic terror threats to go unnoticed.

These surveillance programs that were created as a response to 9/11 continue to focus primarily on Islamic terrorism almost 20 years after the event. The fear of “Muslim terrorists” that shaped post-911 NSA programs still shape the administration’s attitudes towards national security, even though immigrant-linked terrorist attacks are actually highly uncommon. A study by Alex Nowrasteh of the Cato institute reports that the average likelihood of an American being killed in an immigrant-linked terrorist attack is one in 3.6 million. It also shows that 98.6 percent of the deaths from immigrant attacks in the U.S. from 1975-2015 happened during 9/11. Today, domestic terrorism has replaced international terrorism as the greatest terror threat to America. And often, these large-scale government programs aren’t designed (or legally allowed) to find these domestic threats unless they do so “incidentally.” Even though the Department of Homeland Security has admitted that white nationalist domestic terrorism poses a serious threat to the safety and well-being of American citizens, There is currently no domestic terrorism prevention legislation, only an act introduced in the Senate in March 2019.

While some U.S. citizens now deliberate over whether or not they should purchase a laptop cover, one minority group in particular has been ruthlessly targeted by the NSA’s surveillance for as long as most of its existing programs have been around. In Snowden’s leaks, a spreadsheet was revealed that included the names of five extremely prominent Muslim-Americans. This document indicated that these people were “not only agents of an international terrorist organization or other foreign power, but also ‘are or may be’ engaged in or abetting espionage, sabotage, or terrorism.” This list included Faisal Gill, a Republican member of the Department of Homeland Security under President Bush. Snowden’s leak also revealed an invented character named “Mohamed Badguy,” appearing in an NSA document created to demonstrate how to query a database in order to track communications. This paranoia has carried over into recent years. A study from Georgia State University found that terror attacks by Muslim Americans get 357 percent more media coverage than incidents perpetrated by members of other faiths and that “members of the public tend to fear the ‘Muslim terrorist’ while ignoring other threats”.

The NSA’s Orwellian programs can’t be functional in the America of today. The fear of making another security-related error similar to that involving the 9/11 attacks has allowed the power of these programs to spiral out of control. Instead of protecting the country from legitimate threats, the NSA may have instead contributed to the rise of domestic terrorism in recent years. Post- 9/11 fear has manifested itself in more aggressive patriotism, which has sometimes mutated into domestic terrorism against minority groups such as Muslim-Americans. This poses a bigger question: how can we retain the right to privacy guaranteed to us in the Fourth Amendment when the bigger threat to our safety resides in our home country?

To heal the damage of a post-9/11 America, these programs, which have proven themselves dysfunctional, must be reformed. The U.S. desperately needs domestic terrorism prevention legislation to publicly condemn a more imminent threat. America need not spy on its citizens, but they must adapt to the present by surveilling present threats, not “Mohamed Badguy.” The NSA’s surveillance programs should not infringe on the privacy of citizens, to guarantee their Fourth Amendment rights. Surveillance is essential in combating threats to the country- in no way should it be eliminated completely- but the way in which it is implemented must not distract citizens and government officials from the true identity of these threats.